A thoughtful conversation emerged after the Saturday evening (01/05/13) screening of this alarming film which detailed the plight of ocean life due to over fishing of our oceans. Fish populations are in severe decline with some experts in the film predicting a seafood crisis by the year 2050. One suggestion for countering this trend is to eat small fish. Much like it takes 54 kilos of grain to produce one kilo of beef, it takes 50 kilos of small fish (like sardine or anchovy) to produce one kilo of larger fish like salmon. Because of this, it is better to eat the smaller fish directly. Small fish also require less time to reproduce and contain less mercury than larger fish. Another idea is to be an informed consumer. You can make informed buying decisions by not ordering fish that are on the endangered species list, asking your grocer or server if the fish on offer was sustainably caught or farmed. You can also look for and purchase Marine Stewardship Council Certified Sustainable Seafood.

Some interesting facts presented in the film include that, despite increased number of fishing vessels, industrial technology and area fished, the worldwide catch has been declining since the late 1980s. When scientist propose catch limits that would help populations recover, politicians often ignore them and allow an unsustainable number of fish to be brought to market each year. In fact the organizations that police the international fishing industry allow that 99.6% of the ocean to be fished. That leaves a mere 0.04% of protected aquatic habitat. It is estimated that in order to allow populations to recover we would need to protect least one-third (33%) of our oceans.

After the film, engaged Queens Library patrons shared thoughts on the film and expanded the conversation to include topics that where not thoroughly explained in the film. These included the melting of icebergs resulting in the acidification of our oceans, massive amounts of plastic in the oceans causing multiple problems and the FDA's recent approval of the first genetically modified organisms in the animal kingdom allowed into our food system in the form of AquaBounty GMO salmon. There are lots of things to be aware of and coming together as a community to learn and discuss these things is important so we can collectively address the issues we are faced with.

The New York Times reported that recently — just off the island of Midway, where the pivotal naval battle of the Pacific War was fought 71 years ago — archaeological divers discovered the remains of an historical rarity.

In 10 feet of water, they found the propeller and other broken, rusted pieces of a Brewster Buffalo, one of the fighter planes flown by the U.S. Marine Corps from the naval base at Midway up until the battle.

Those sad pieces, along with everything else erased by hard impact and decades of corrosion, came from Queens — Long Island City, in fact.

The Brewster Buffalo was the U.S. Navy’s first single-seat monoplane fighter. While it wasn’t exactly sleek, it was fast for its time — and a coup for Brewster, a former carriage and automobile manufacturer, which scored the contract against big-name competitors like Grumman. Brewster converted its factory at 27-01 Queens Plaza North and started cranking out the squat planes.

The Buffalo was a big deal when it entered service around 1938, but it was pitifully obsolete by the time Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941. In fact, the plane’s landing gear proved too weak to land on aircraft carriers, so the planes were shunted off to the Marines for use on land bases.

The Marines hated the Buffalo, which was outmatched by the Japanese Zero. When Japanese planes attacked the Midway airbase during the battle, aviators flying the Buffalo were decimated. In the book Semper Fi in the Sky, author Gerald Astor quotes the report of one pilot, Marine Capt. Phil White: “Any commander who orders pilots out in [a Buffalo] should consider the pilot lost before leaving the ground. It is inferior to the planes we are fighting in every respect.”

The Buffalo was quickly phased out by the Navy and Marines, but it was embraced by Finland, which used them with great success against the air force of the invading Soviet Union in 1941. In fact, the world’s only remaining Brewster Buffalo was fished out of a Finnish lake in 1998.

And the company? According to information in our Archives, it started in the early 19th century, but did not last much beyond the Buffalo’s disastrous combat debut. Fraught with mismanagement but fueled by massive military contracts, Brewster built a huge new factory in Bucks County, Pennsylvania to build a new dive bomber for the Navy. Its production was so wracked with embezzlement and union disputes that the company spent much of the war under government management or congressional investigations. The company dissolved in April 1946, its place in history assured by the stubby, finicky little plane from Queens that flopped in the Pacific but soared in Nordic latitudes.

The old factory in Long Island City has a new and more successful claim on aviation these days: JetBlue’s headquarters is now located there.

Want to learn about successful New York airplane makers? You’ve got to look at Long Island. Grumman and Republic, two of the biggest names in military aerospace, both operated factories there.

The week of January 7 marked the start of a new season of a certain popular television series about a federal marshal and the colorful criminal underworld in the rural county he calls home. While you can enjoy the show without knowing much about its origins, its protagonist is the creation of a dizzyingly prolific writer named Elmore Leonard, whose masterful career in genre fiction spanned more than 50 years. Leonard died August 20, 2013 at age 87, leaving behind a massive legacy for writers of crime fiction and westerns.

Born in New Orleans and a Detroit resident since 1934, Leonard got his start writing Western stories in the 1950s (the film 3:10 to Yuma is an adaptation from one of his early successes). He gradually transitioned into writing amusingly hardnosed stories about American lowlifes. His novels are populated with eccentric characters: exotic dancers, small-time gangsters, con men, bookies, and shady lawmen. And the opportunistic, mercenary charm of these characters has translated into 19 cinematic adaptations, including Get Shorty, Out of Sight, Jackie Brown and Mr. Majestyk.

For stories about the Raylan Givens character as Leonard wrote him before the hit TV series, check out Pronto and Riding the Rap.

January 20 marks the 127th anniversary of the patenting of the roller coaster. These scream-inducing attractions have spread all over the world and endured their own peaks and troughs of popularity, but you can’t tell the story without talking about Queens, where a pioneer of the craft brought his final designs.

LaMarcus Adna Thompson filed the original roller coaster patent in 1885. At that point he had already built a “scenic railway” attraction at Coney Island in 1884, consisting of two towers and a dip in the middle.

He based the design on gravity railways such as the Mauch Chunk Rail Road in Pennsylvania, which ferried coal from a company mine to its chutes on the Lehigh River, relying on gravity to propel the carriages along the track. Mules were required to tow the carriages 9 miles back up to the mine and then ride the trains back downhill, sharing the twists, turns and scenic thrills with their drivers.

Thompson’s Coney Island ride was a hit. It touched off a roller coaster arms race of sorts. Among the advancements was the “Drop the Dip,” which burned to the ground in 1907, was rebuilt, and came to be regarded by some as the first modern “high-speed” coaster. The Coney Island coaster that remains, the legendary Cyclone, was built in 1927 on the site of Thompson’s first scenic railway. It’s one of the few wooden roller coasters still in operation, though several replicas pay homage to it around the world.

Thompson wound up taking his big ideas to Queens, where his efforts paved the way for the lost, lamented Rockaways’ Playland. In 1901, Thompson had built a new scenic railway at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. But his business prospects were dashed when President William McKinley was assassinated there. According to Richard Geist, whose family ran Playland for decades, Thompson was enticed to bring the entire elevated railway to an existing amusement park at Far Rockaway. It became known as the L.A. Thompson Amusement Park. A picture in our Archives depicts one of the scenic railways constructed at the location, its support beams appearing to plunge straight into the surf.

The park soldiered on until 1928, two years after the amusement impresario died. At that point the park was sold to the Geist family, who changed the name to Rockaways’ Playland and commenced several decades of financially tenuous operation. Their Atom Smasher coaster was built in 1939 to coincide with the roller coaster on the midway at the World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows Corona Park. It was a central attraction for years, appearing in the 1952 film Cinerama. After Playland closed for good in 1985, the old roller coaster was the centerpiece of the dramatic dismantlement process, as seen above in our Archive photo, making way for condominiums.

Roller coasters had it rough throughout the country in the mid-20th century. Queens was home to other amusement parks that have since vanished from the landscape, like Fairyland, which closed in 1968 to make way for the Queens Center Mall, and Adventurer’s Inn, which was roughly where the New York Times printing plant is now on the Whitestone Expressway — and was condemned by the city in 1973.

Most of the coasters on Coney Island were also razed to make way for development. But The Cyclone lives on, a relic of the heady era Thompson ushered in, and proof that the twists, turns, and rapid plunges of a well-constructed coaster offer thrills that never get old.

Want to learn more about Coney Island? Check out this documentary.

January 15 marks the birthday of one of the greatest drummers of all time: Gene Krupa.

Born in Chicago in 1909, Krupa had been groomed for the priesthood by his parents, but decided to go his own way. He started playing the instrument in the 1920s and his powerful, busy drumming style came to the foreground in the 1930s, the heyday of what’s known as “big band” jazz.

You might know his drumming best from the classic Benny Goodman rendition of “Sing, Sing, Sing,” featured in countless films about the 1930s and World War II, available here in this 1938 Carnegie Hall performance. Krupa’s heavy rolls on the toms gives a burly, ominous underpinning to the soaring brass and woodwinds.

Krupa’s style helped define the era, but his fame faded some as the size of popular jazz combos shrank after World War II. He enjoyed a resurgence in the 1950s, including a film about his life, and retired in the 1960s, opening a music school and playing the occasional show.

Krupa died in 1973, but his influence is monumental among drummers, even outside of jazz. KISS drummer Peter Criss trained at Krupa’s school, while Neil Peart of the prog rock band Rush has paid explicit tribute to Krupa at concerts. He pops up occasionally in pop culture, such as the street drummer in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, advertising his ability to play in Krupa’s style. In a film wallowing in the debauchery and sleaze of 1970s New York, the Krupa mention is a brief, melancholy callback to a more elegant time in the city’s history.

Krupa’s drum set is now enshrined at the Smithsonian, alongside that of his friendly competitor Buddy Rich, with whom Krupa held several “drum battle” concerts, starting in 1952.

Want to learn more about Gene Krupa? Check out his biography.

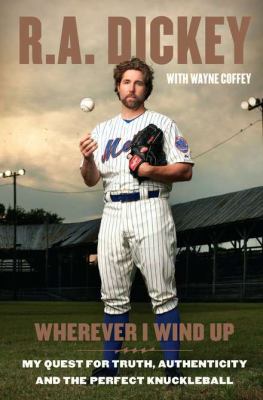

I recently read Wherever I Wind Up: My Quest for Truth, Authenticity and the Perfect Knuckleball by New York Mets pitcher and Cy Young Award winner R. A. Dickey. Mr. Dickey’s story is not the typical athlete’s tale of success. He had many obstacles in his upbringing to overcome, including the divorce of his parents, sexual abuse, physical ailments that affected his ability to pitch, and more. His story is very inspirational, and a really good read. I highly recommend this book for those who enjoy stories about athletes, as well as for those who just want to be inspired by an individual’s spirituality and commitment to a goal. And winning the Cy Young Award for his pitching success this past season really put the cherry on the sundae!

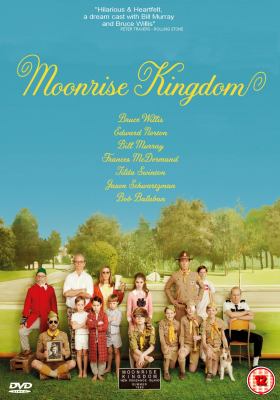

The houses in Moonrise Kingdom look like advent calendars, tiny compartments filled with toys. There are bird costumes and a raccoon cap and an ancient phonograph that runs on batteries. You can see every room, because the camera never stops moving, as though the director, Wes Anderson, were afraid he might miss something. You begin to suspect that Anderson thinks of the whole world as a cabinet of wonders. The story has to do with a boy and girl who run away into the woods, where they camp out in the world's smallest tent. Everything that happens is completely implausible, so I believed it utterly. When I left the movie theater, I passed a vendor selling ginger juice and a woman from an animal shelter who was surrounded by tiny cats. I thought: Wes Anderson has found a way to production-design New York. When you see the movie, you may want to watch it on freeze-frame, so you can ask the same question you ask about a cabinet of wonders: How did they do that?

Since our move to the country a little over a year ago, we have been fortunate enough to have lots of land, which meant that we could have an even bigger garden than we had in our plot at the Community Garden in Great Neck. This turned out to be a very good thing, because I find myself becoming more and more allergic to the preservatives and additives food companies seem to be using these days.

So I turned to my new garden with a fresh eye. We planted this year and had so many cucumbers, tomatoes (24 plants!), butternut squash, zucchini, green beans, lima beans — the list goes on and on.

I had not planned for such a bountiful harvest. Fortunately, the house’s previous owner had left behind a book on canning, and it opened up a whole new world for me.

Canning is a wonderful world within itself. Not only can you can fresh fruits and vegetables for the winter, you can also can whole meals, meats, beans, and casseroles for those nights you just don’t feel like cooking. And they stay preserved without the use of chemicals. The possibilities are endless.

Queens Library offers dozens of books on home canning. A great, widely celebrated place to start would be the Ball Corporation’s Complete Book of Home Preserving. They’re the company that manufactures the jars you’ll probably be using. The book offers 400 recipes for beginners and experienced home canners. They also offer classes around the United States, and an online forum to hear of folks’ successes and failures.

I started my new adventure with the cucumbers. It wasn’t hard to follow the recipe for the pickling spice — the challenge was getting a flavor that we liked! I tried a variety of batches until I found the right combination. My friends and neighbors were very happy to inherit our experimental batches! You might try some of the recipes from this well-regarded book to get you started.

Next I moved onto the problem of 24 tomato plants, all ripening almost at the same time. That was quite the task. Tomatoes can’t just be thrown into brine and given a water bath. They have to be boiled for a few seconds so that the skins peel off, and you have to remove the seeds. Once you have finished this labor-intensive stage, you purée your tomatoes and make gravy or sauce as you would normally. The real secret is letting this sauce cook down for 4 to 6 hours to reduce the water content. Once it’s cool enough to handle, you fill your jars, and put into your canner or pressure canner for 30 minutes or so.

I canned over 80 pounds of tomatoes this fall, and it was worth every minute of my time, from planting the seeds in the ground, to nurturing and watering the garden, to the wonderful harvest! Now I have plenty of tomato sauce for quick meals after a hard day at work.

If pickling really captivates you, you might also want to check out this free cooking demonstration from kimchi wizard and cookbook author Lauryn Chun at the Flushing Library on January 7 from 6:30 to 7:45.

Curious for more? Here’s one of my favorite canning recipes:

Ellen Hayes’ Split Pea Soup (This is a large batch, so you can cut the recipe if you need to)

4 large carrots, chopped

1/2 stalk celery, chopped

4 cans chicken broth

10 cups water

2 cloves garlic, minced

1.5 tbsp onion powder or 1 cup onion diced

2 tsp salt

1 tsp pepper

2 lbs of rinsed, dried green peas

1 bay leaf

1. Combine all ingredients in a large pot, bring to boil.

2. Reduce heat and simmer covered till peas, carrots and celery are all tender (about 2 hours). You may have to add more liquid.

3. You can purée the mixture if you wish. I didn’t.

4. Pour into hot quart jars and seal. Process 90 minutes at PSI suited to your altitude. Yields 7 Quarts.

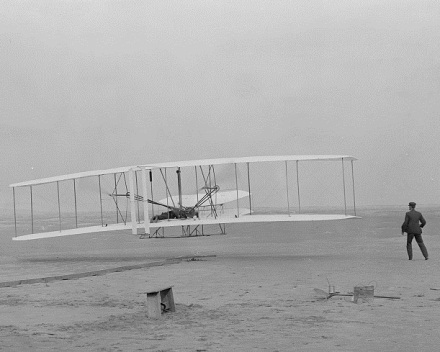

December 17 is a big day for aviation history. In 1903, Ohio bicycle makers Orville and Wilbur Wright took their homemade craft down to Kill Devil Hills in North Carolina and became the first to achieve manned, controlled heavier-than-air flight.

The Wrights’ story is well-known thanks to their inclusion in history textbooks, but their success was not preordained. It’s easy to think of their achievement as an isolated and peculiar step forward in a whimsical and quaint era, but manned flight was the tech frontier of the day. Much like today’s internet startups are jockeying to harness the revenue power of social networking, dozens of innovators around the world were racing to harness the power of airflow over a flat surface.

The Wrights had rivals in France and in South America. But their most visible threat was from Samuel Langley, director of the Smithsonian. Langley had successfully flown scale models of his “Aerodrome” craft several years before the Wrights’ triumph. But despite thousands of dollars in government funding, Langley’s design was not robust enough to handle the strains of full-scale, manned flight. It crashed twice in 1903, the second time little more than a week before the Wrights made history with their meticulously tested craft.

The Wrights ushered in a new era in transportation—a massively profitable one for those with the knowhow. The Wrights were issued a patent for their flying machine in 1906, and shortly thereafter, they sued another early aviation titan, Glenn Curtiss, for copying their flight controls and wing designs (think of it as a historical predecessor to the Apple/Samsung patent battle currently raging). The fight lasted until 1918, and even involved an unsuccessful attempt to discredit the Wrights by showing that Langley’s contraption could have worked. That endeavor had the backing of Henry Ford and Langley’s successor at the Smithsonian.

You can now see the Wright Flyer at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, but it took decades before Orville Wright would hand over his monumental machine to an organization that had supported his rivals.

Not coincidentally, December 17 marks another aviation milestone: On that day in 1935, the Douglas DC-3 first flew. The airplane is perhaps not as famous as World War II fighters like the P-51 Mustang or stealth jets like the B-2 bomber, but its importance and longevity are essentially unmatched.

The DC-3 was the first commercial airliner that was cost-effective enough to allow struggling airlines to operate without federal Air Mail subsidies. It set a standard for commercial aviation in the 1930s before its reputation for reliability and toughness was earned in battle.

When World War II broke out, the DC-3 was built for the military as a cargo plane and troop hauler. It served in every Allied military, and was even copied by the Japanese. It was the primary airplane that dropped paratroopers behind enemy lines in the hours preceding the D-Day landings in 1944. It flew cargo over mountain ranges to isolated Allied bases in Asia. Dwight Eisenhower wrote that it was one of the six pieces of equipment most important to the Allied victories in Europe and Africa.

The DC-3 continued to serve the U.S. military through the Korean War and even Vietnam. In civilian life, countless surplus DC-3s became airliners in developing areas like South America, where short, unpaved airfields were the norm. Unsurprisingly, the plane’s toughness and availability also made it a favorite of drug smugglers. Nearly seven decades after the last DC-3 rolled off the assembly line, several hundred continue to fly today, some still in commercial service.

Interested in other tales of aviation innovation and daring? Check out this book about the challenges and triumphs of designing the Boeing 747, written by the project’s chief engineer. Read about the larger-than-life personalities competing to be the first to fly nonstop across the Atlantic in 1927. Read about Amelia Earhart’s combination of bravery and media savvy. Or read Tom Wolfe’s classic The Right Stuff, about test pilots, astronauts and the space race.